The Premises

Most departments of Basel University are located in the heart of the old city. The Department of English is housed in two adjacent buildings on Nadelberg, two minutes from the market square. The oldest of these, at the back of a cobbled courtyard, is also the oldest stone building in Basel. It was already called "Schönes Haus" ("Beautiful House") when it was first mentioned in a document in 1294, because of its wealth and decorative splendour. For centuries it continued to be the home of rich citizens, among them Rudolph Wettstein, who represented the Swiss at the Peace of Westphalia negotiations in 1648; the coat-of-arms over one of the portals is that of the Karger family, who owned the building in the 17th and 18th centuries. During the Council of Basel (1431-49) church dignitaries were entertained in the great hall on the ground floor, notable for its painted ceiling (the oldest non-ecclesiastical one in Switzerland); it serves as a lecture theatre today. Guests lodged in the building included Duke Philip of Burgundy (1454), Duke Albrecht of Bavaria (1473), and Prince John of Orange (1479).

In the 1960s the buildings were carefully restored, and given to the university in 1968. In one of the rooms, which now serves the department as a library, a Gothic wooden ceiling saved from the ruins of another building was added. The cellar of the "Schönes Haus" was converted into a studio theatre, seating about 100 people, which is run by the department.

Today, with the growth of the department over the last few decades, the buildings have almost become too small. But their atmosphere continues to outweigh any such disadvantages.

References

Sommerer, Sabine (2003). «Wo einst die schönsten Frauen tanzten...». Die Balkenmalereien im «Schönen Haus» in Basel. Neujahrsblatt der GGG Nr. 182 / 2004. Basel: Schwabe (ISBN 3-7965-2010-3).

English at Basel University – A Historical Note

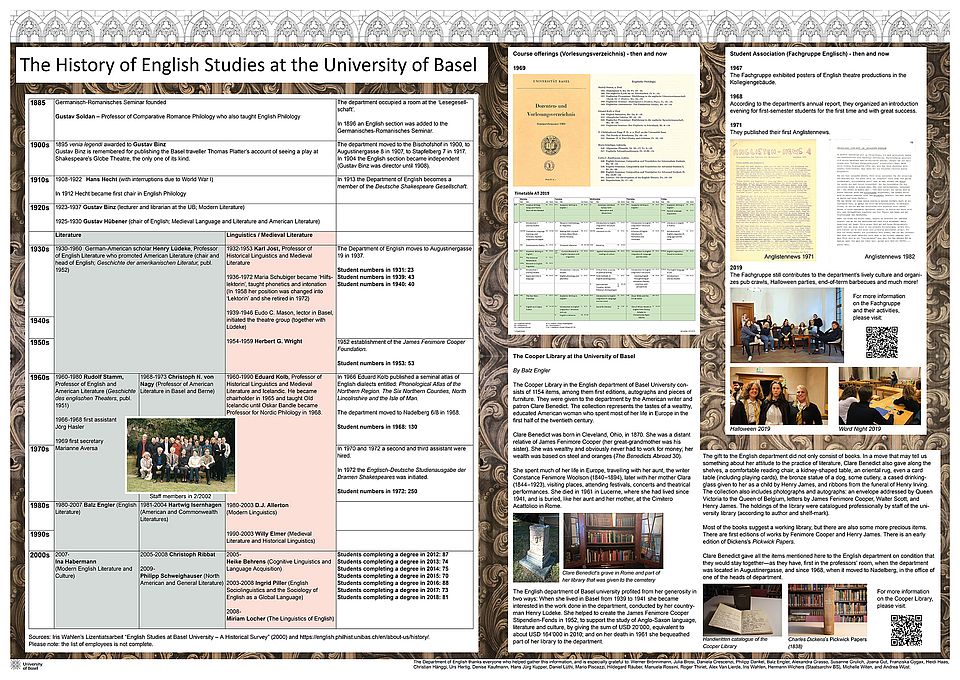

Basel University was founded in 1460. But, as elsewhere, it was only in the nineteenth century that modern languages began to play an important role in the curriculum. In 1885 the Germanisch-Romanisches Seminar was founded, with the express purpose of promoting both research and the training of language teachers. English was then a marginal field; it was taught intermittently by the Professor of Comparative Romance Philology, Gustav Soldan. In 1900 Gustav Binz was awarded a professorship in English philology; he taught courses mainly on Old English language and literature, and is remembered for publishing the Basel traveller Thomas Platter's account of seeing a play at Shakespeare's Globe Theatre, the only one of its kind.

After Binz's departure, Hans Hecht, a biographer of Burns, was appointed in 1911, but he was away most of the time during the First World War, serving in the German army. In 1922 he accepted a professorship in Göttingen. Only in 1925 was the post filled again, by Gustav Hübener (who had come from Königsberg, and moved on to Bonn in 1930). In the meantime, Binz had been given a professorship ad personam in 1923, which he held until 1932, along with the position of an "Oberbibliothekar" at the University library. From 1925, there were then two professorships, one in medieval language and literature, one in modern literature – an arrangement that lasted until 1980.

Stability in the development of English as a discipline came with the establishment of the Englisches Seminar in Augustinergasse (1937) and the appointment of the German-American scholar Henry Lüdeke in 1931. At a time when this was by no means a matter of course, he gave due weight to American literature in his teaching (and published an influential Geschichte der amerikanischen Literatur in 1952). In 1960 Lüdeke was followed by Rudolf Stamm, whose interest was mainly in Shakespeare and the theatre (note his Geschichte des englischen Theaters of 1951); he made sure that the department got its own theatre when it moved to Nadelberg in 1968. In 1980 Balz Engler took over from Rudolf Stamm; he retired in autumn 2007, and was followed by Ina Habermann, who was appointed as the first female chair of Modern English Literature and Culture.

In historical linguistics and medieval literature Karl Jost taught from 1932-1953. He was followed by Herbert G. Wright (1954–1959), Eduard Kolb (1960–1990), a specialist in English dialects (and the editor of two atlases in the field), and Willy Elmer (1990–2003).

In the early eighties, with rapidly rising student numbers, two new professorships were created, one in modern linguistics held by D.J. Allerton (1980–2003), and one in American Literature held by Hartwig Isernhagen (1981–2004), Christoph Ribbat (2005–2008) and currently by Philipp Schweighauser.

In 2005, linguistics at the Department were re-defined by the creation of two new Chairs, one in English Sociolinguistics and in the Sociology of English as a Global Language, and the second in Cognitive Linguistics and Language Acquisition, now held by Miriam Locher and Heike Behrens respectively.

The history of a discipline is obviously not just the history of the persons appointed to teach it. It is also the writing of the history of an institution; Iris Wahlen, a former student of English, chronicled this institutional history in her Lizentiatsarbeit entitled English Studies at Basel University: A Historical Survey.

References and Additional Information

Bonjour, Edgar (1960). Die Universität Basel von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart, 1460–1960. Basel: Helbing & Lichtenhahn.

Finkenstaedt, Thomas (1983). Kleine Geschichte der Anglistik in Deutschland. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Kreis, Georg (1986). Die Universität Basel 1960-1985. Basel: Helbing & Lichtenhahn.

The Cooper Library at the University of Basel

By Balz Engler

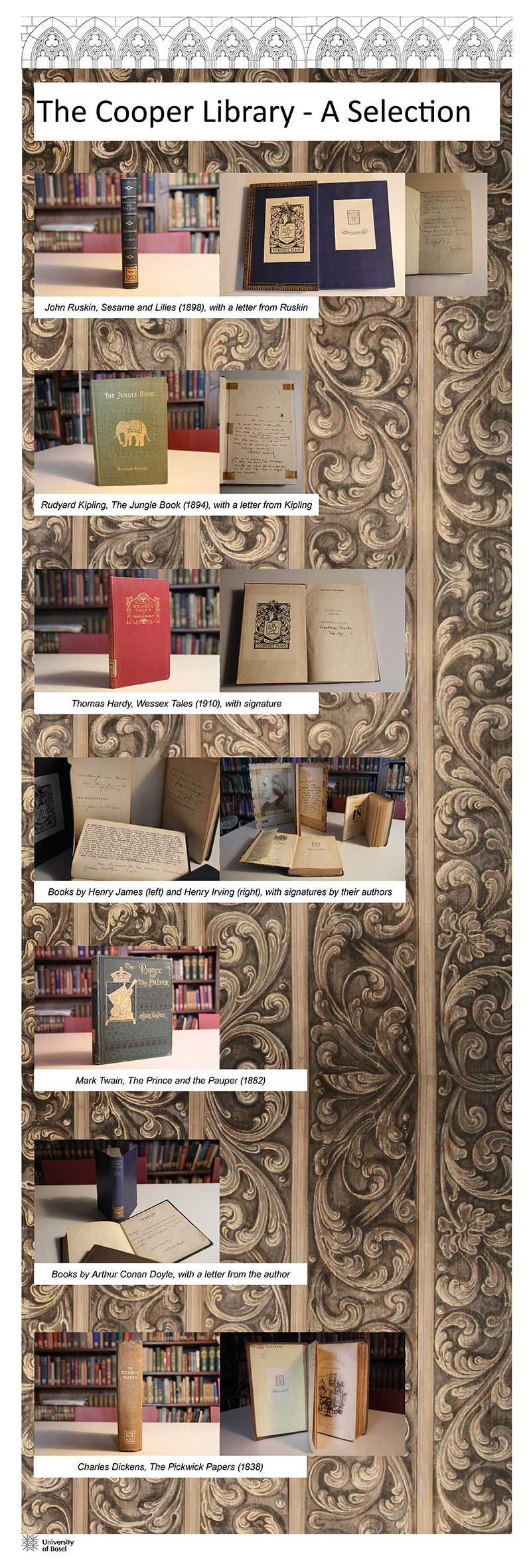

The Cooper Library in the English department of Basel University consists of 1154 items, among them first editions, autographs and pieces of furniture. They were given to the department by the American writer and patron Clare Benedict. The collection represents the tastes of a wealthy, educated American woman who spent most of her life in Europe in the first half of the twentieth century.1

Clare Benedict2 was born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1870. She was a distant relative of James Fenimore Cooper (her great-grandmother was his sister). She was wealthy and obviously never had to work for money; her wealth was based on steel and oranges (The Benedicts Abroad 30).

She spent much of her life in Europe, travelling with her aunt, the writer Constance Fenimore Woolson (1840–1894), later with her mother Clara (1844–1923), visiting places, attending festivals, concerts and theatrical performances. She died in 1961 in Lucerne, where she had lived since 1941, and is buried, like her aunt and her mother, at the Cimitero Acattolico in Rome.

Clare Benedict was a gifted writer, who published collections of tales, A Resemblance: And Other Stories (1909), XII (1921), and other books like European Backgrounds (1912), The little lost Prince (1912), The Divine Spark (1913) on Wagner, Six Months, March to August, 1914 (1914), a personal account of the months leading up to the war, and, Five Generations: 1785–1923 (1930), consisting of the three volumes Voices Out of the Past, Constance Fenimore Woolson, and The Benedicts Abroad.

But Clare Benedict is perhaps best remembered as a patron, in various areas. Wikipedia mentions her only as the person who made possible the Clare Benedict Chess Cup, an international chess tournament, which was held from 1953 to 1979, when, apparently the funds ran out (Olimpbase). Other engagements may have been more important: After World War I she started to support the Schillerstiftung with generous gifts of food for needy writers3. She did the same again after World War II, and in 1950 helped, with a generous donation, to put the Schillerstiftung on its feet again. The Stiftung had apparently become some kind of surrogate family to her (Schwabach-Albrecht, Schillerstiftung 66–67).

In 1923, when her mother died she gave funds to the Cimitero Acattolico in Rome to raise the wall around it and for gardening (Schwabach-Albrecht, Clare Benedict 66). In 1938, Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, with her help, could open Woolson House, and install The Clare Benedict Collection of Constance Fenimore Woolson there, which also contains documents relating to Clare Benedict’s life (Rollins College).

For reasons I have not yet been able to establish, there is also a tulip that carries her name: Tulipa eichleri 'Clare Benedict’.

Finally, and crucially in this context, the English department of Basel university profited from her generosity in two ways: When she lived in Basel from 1939 to 1941 she became interested in the work done in the department, conducted by her countryman Henry Lüdeke. She helped to create the James Fenimore Cooper Stipendien-Fonds in 1952, to support the study of Anglo-Saxon language, literature and culture,4 by giving the sum of USD 20’000, equivalent to about USD 164’000 in 2010;5 and on her death in 1961 she bequeathed part of her library to the department. This will be described in more detail below.

Books obviously played an important role in her life. When she and her mother definitely moved to Europe in 1921 she had her library sent along, and she continually added to its holdings, also keeping guidebooks and brochures about places she had visited. When she began to give away part of it, she produced several catalogues, listing the books according to thematic criteria. These hand-written lists, nicely bound, are now part of the Cooper library.6

The library at Basel does not represent the full range of Clare Benedict’s books. She obviously felt, late in her life, that the books associated with people buried at the Cimitero Acattolico in Rome should also be represented there. In 1960, shortly before her death, she put together a catalogue of the books she gave to that cemetery, a stencilled volume that also offers short texts by her and by others, explaining the association between them and the cemetery (Benedict, In Memoriam). It is doubtful that the books are still there.7

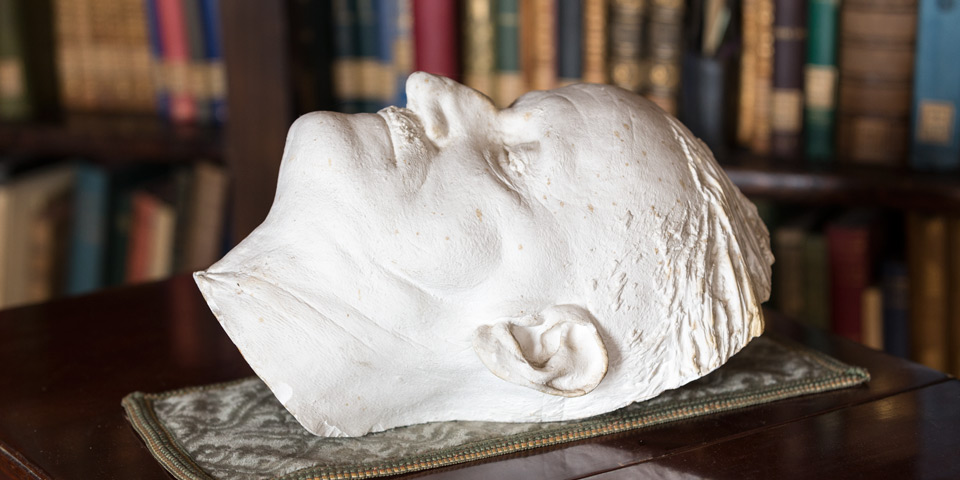

As was the case with Rollins College, the gift to the English department did not only consist of books. In a move that may tell us something about her attitude to the practice of literature, Clare Benedict also gave along the shelves, a comfortable reading chair, a kidney-shaped table, an oriental rug,8 even a card table (including playing cards), the bronze statue of a dog, some cutlery, a cased drinking-glass given to her as a child by Henry James, and ribbons from the funeral of Henry Irving. The collection also includes photographs9 and autographs: an envelope addressed by Queen Victoria to the Queen of Belgium, letters by James Fenimore Cooper, Walter Scott, and Henry James.10

The holdings of the library were catalogued professionally by staff of the university library (according to author and shelf-mark).11 Among the 1154 items, which cover a wide range of topics, there are collections of newspaper clippings on Henry Irving and George Meredith.12 There are playbills of the performances Clare Benedict had seen all over Europe. There are musical scores. There are editions of Anglophone classics, many of them in editions from the first half of the twentieth century. There are guides to (mainly) Italian towns and churches. There are biographies. There are publications that had been given to Clare Benedict, among them probably the impressive Folio Die Holzarten im mittleren und nördlichen Deutschland. In its variety the library represents the interests of an educated American expatriate lady with a voracious interest in European culture.

Most of the books suggest a working library, but there are also some more precious items. There are first editions of works by Fenimore Cooper13 and Henry James.14 There is, according to the catalogue, an early edition of Dickens’s Pickwick Papers.15

Clare Benedict gave all the items mentioned here to the English department on condition that they would stay together—as they have, first in the professors’ room, when the department was located in Augustinergasse, and since 1968, when it moved to Nadelberg, in the office of one of the professors at the department.

References

Benedict, Clare. A Resemblance: And Other Stories. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1909.

Benedict, Clare. XII. Leipzig: Tauchnitz, 1921.

Benedict, Clare. European Backgrounds. Edinburgh: Andrew Eliot, 1912.,

Benedict, Clare. The little lost Prince. Edinburgh: Andrew Eliot, 1912.

Benedict, Clare. The Divine Spark. Privately printed, 1913.

Benedict, Clare. Six Months, March to August, 1914. Cooperstown NY: Arthur H. Crist Co. 1914.

Benedict, Clare. Five Generations: 1785-1923 (1930), vol. 1-3. Voices Out of the Past, Constance Fenimore Woolson, The Benedicts Abroad. London: Ellis, 1930.

Benedict, Clare, ed. The In Memoriam Library Selected and Edited by Clare Benedict. Lucerne 1960. (Cooper 251)

Hasler, Jörg. Switzerland in the Life and Works of Henry James. Cooper Monographs, 10. Berne: Francke, 1966.

Olimpbase: https://www.olimpbase.org/1979q/1979in.html (20-8-2020)

Rollins College: https://lib.rollins.edu/olin/oldsite/archives/benedict.htm (20-8-2020)

Schwabach-Albrecht, Susanne. „ Clare Benedict (1870-1961): Schriftstellerin und Stifterin: ein Porträt“ In: Deutsche Schillerstiftung von 1859:Ehrungen, Berichte, Dokumentationen 1997. Ed. Michael Krejci. Fürstenfeldbruck:. Kester-Häusler-Stiftung, 1997. 60-86.

Schwabach-Albrecht, Susanne, „Die Deutsche Schillerstiftung 1909-1945“. Archiv für Geschichte des Buchwesens 55 (2001). 1–156.

Stöcklin, Elisabeth. “Clare Benedict and the Cooper library at the English Seminar, Basel University”.M.A. thesis, Basel University, 1982.

Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clare_Benedict (06-02-2011)

Footnotes

1 Its holdings have been analysed by Stöcklin 1982. The thesis is available at the department, shelf mark “ENG Liz 1982/2”.

2 She should not be confused with the later writer of Rainbow Romances of the same name.

3 She was made a honorary member in 1923.

4 See the appendix for its rules.

5 A person who was instrumental in arranging for this gift was Carl Burckhardt-Sarasin (14.12.1873-30.4.1971), a ribbon manufacturer, who had befriended Clare Benedict in his open house. He collected books and prints, and supported the arts and social institutions. His photograph, for good reason, is also part of the Cooper Library.

6 Catalogue of English and American classics for the English Seminary of Basle University. Handwritten (Cooper 109); Cooper Catalogue. Handwritten (Cooper 472); Clare Benedict Collection. Another handwritten list by CB. Ordering books mainly according to geographical topics. But also music (Cooper 125); The In Memoriam Library Selected and Edited by Clare Benedict. Stencilled. Lucerne 1960 (Cooper 251).

7 Inquiries with the Keats-Shelley House in Rome have not led anywhere.

8 This seems to be precious. According to anecdote, Siegfried Korninger, professor at Vienna, and a collector of rugs, fell on his knees on entering the room.

9 One is of Clare Benedict herself, two of Lamb House in Rye, Sussex, where Henry James lived from 1897.

10 These 28 letters are now in the manuscript department of Basel University Library. They have been published in Hasler.

11 The catalogue is to be found in the library itself and as a pdf document [PDF (1.1 MB)]

12 The Lyceum Collection Henry Irving Cooper 13;George Meredith (no shelf-mark).

13 The Pioneers 1823 (Cooper 152), Lionel Lincoln 1825 443 (Cooper 444), The Prairie 1827 (Cooper 447), The Red Rover 1827 (Cooper 455), The Water Witch 1830 (Cooper 456), The Bravo 1831 (Cooper 75), The Heidenmauer 1832 (Cooper 458), The Headsman 1833 (Cooper 451), Gleanings in Europe 1837 (Cooper 77), Excursions in Switzerland 1838 (Cooper 72), The Deerslayer 1841 (Cooper 78), Lives of Distinguished American Naval Officers 1846 (Cooper 459)

14 Transatlantic Sketches 1875 (Cooper 56), French Poets and Novelists 1878 (Cooper 62), Hawthorne 1879 (Cooper 210), Washington Square1881 (Cooper 42), Stories Revived 1885 (Cooper 39), The Bostonians 1886 (Cooper 37), The Princess Casamassima 1886 (Cooper 38), The Aspern Papers 1888 (Cooper 44), The Reverberator 1888 (Cooper 45), Partial Portraits 1888 (Cooper 58), A London Life 1889 (Cooper 46), The Tragic Muse 1890 (Cooper 50), The Lesson of the Master 1892 (Cooper 48), The Private Life 1893 (Cooper 51), The Real Thing and Other Tales1893 (Cooper 47), In the Cage 1898 (Cooper 54). Several of these are signed by the author.

15 As of February 2011 this item is missing on the shelves. Dickens, Charles. The posthumous papers of the Pickwick Club. London, 1838 (Cooper 330).